Old Stories from Lucerne

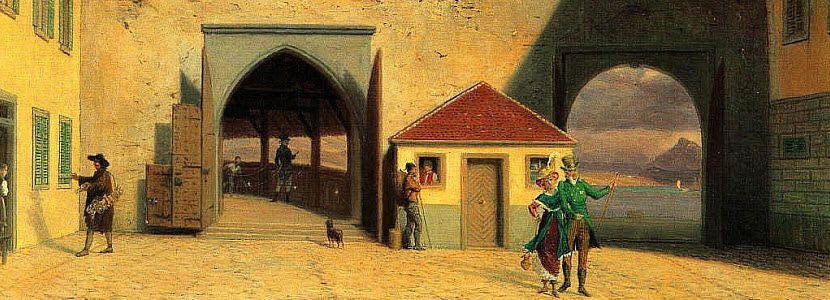

The painting “The Gates to the Hof Bridge and the Boat Landing” by Xaver Schwegler (1832–1902) shows the view from the lower Kapellplatz toward the lake, the way this place looked around 1834 . Schwegler painted the picture around 1900 , using a drawing by his father Jakob Schwegler , who had seen the scene himself. On the right side of the painting is the Zur Gilgen House . Next to it is part of the old city wall with two gateways : The left gateway , with a pointed arch, leads to the Hof Bridge . The right gateway , with a round arch, leads to the boat landing . Through this round arch you can see Mount Rigi in the background.

When you stand at Schwanenplatz in Lucerne, you will notice a special building right away: the house “Zur Gilgen” with its round tower. It stands at Kapellplatz 1 , between the River Reuss and Schwanenplatz — right in the heart of the old town. A medieval tower becomes a stone house Long ago, a wooden defence tower stood here as part of Lucerne’s city walls. After it burned down around 1500, Melchior zur Gilgen built today’s stone house and tower between 1507 and 1510. It is the oldest surviving stone house in Lucerne . Melchior Zur Gilgen was a soldier, military leader, and diplomat. He died of malaria in 1519 on his way home from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and was buried on Rhodes.

This painting is by Joseph Clemens Kaufmann and is dated 1901 ( oil on canvas, 58 × 76 cm ). The artist was probably standing on the Spreuer Bridge when he painted this beautiful scene. It shows the right bank of the River Reuss below the bridge around 1890 . At the centre of the painting stands the Nölliturm , built between 1516 and 1519 , marking the lower end of the Musegg Wall . Because of its bright red tiled roof, it was once called the “Red Tower.” The painting shows a time when the riverside was still quiet, natural, and free from traffic – the St. Karli Quay and the Geissmatt Bridge did not yet exist. The river lies calm in the warm sunlight, the houses reflect in the clear water, and gardens and old trees rise up on the hillside. The whole scene feels peaceful and timeless , as if everyday life had paused for a moment.

Long ago, on Mount Pilatus , there lived little mountain men . They lived inside the whole mountain , from the top down to Hergiswil and the Eigental. They could suddenly come out of caves and disappear again very fast. They were very small and wore green clothes and red hats . Their feet looked like goose feet . They had long white hair and beards down to the ground . They looked after animals and fish and helped the farmers . But if someone was unkind to them, they took revenge very quickly . On the Kastelen Alp , there once lived a rich farmer named Klaus . One day, Magdalena came to him. Her mother was poor and sick . Magdalena asked Klaus for help. But Klaus only laughed at her . So Magdalena walked sadly down the mountain. On the way, she met a farm boy from the Bründlen Alp . He saw how sad she was. So he gave her his only small cheese .

In the valley of the Hilfern , on the western slope of the Schratten near Marbach , there lived a poor widow in a very small and crooked little house. Often she did not know how she could feed herself and her children. She owned only one cow , and in the attic there was just a small, thin pile of hay.

Mount Pilatus strongly stimulated the imagination of the people in Switzerland early on. This was because it seemingly rose gently from the flatlands, but then suddenly jutted steeply upwards in massive rock formations. The ancients called it "Fractus mons" (broken mountain) or Frakmont . They considered it nothing more than a split and broken-up mighty hill. Since the people of antiquity could not explain the elemental forces that once split the mountain, they saw in them the work of evil powers. Because fire, water, storms, and lightning had always terrified the residents, they believed that these forces were causing mischief on the mountain. In the ignorance of the Middle Ages, one thing was clear: spirits lived there. In the stories, one heard of dragons, ghosts, spirits, hobgoblins (Herdmännlein), and mischievous dwarves (Toggelis); even the Türst and the Sträggele caused trouble there.

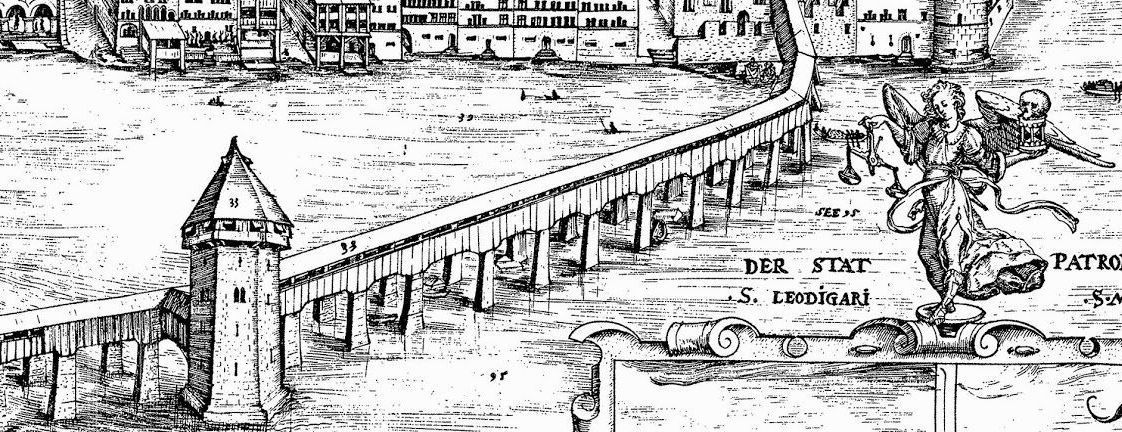

Lucerne, 1758. The Golden Time of the Republic was coming to its autumn. Wars and bad harvests in Europe meant that the soldier contracts, which the city lived from, were paid slowly. This made the state treasury, the heart of the Lucerne Republic, even more important. It was stored in the safest place you could think of: in the upper room of the Water Tower. The Reuss river flowed around it, and you could only reach it over the Chapel Bridge or by boat.

A painting on the Chapel Bridge (panel Nr. 25) once showed a famous Lucerne legend: The Emperor Charlemagne giving special "Harsthörner" (war horns) to warriors from Lucerne to honor them. (Please note: This original painting was unfortunately destroyed in the 1993 Chapel Bridge fire and is no longer on the bridge.) The legend says that in 778, warriors from Lucerne joined Charlemagne’s army in Spain. They bravely saved his nephew, Roland, in a battle. As a "thank you" for their loyalty and courage, the emperor gave them the special war horns, a great privilege.

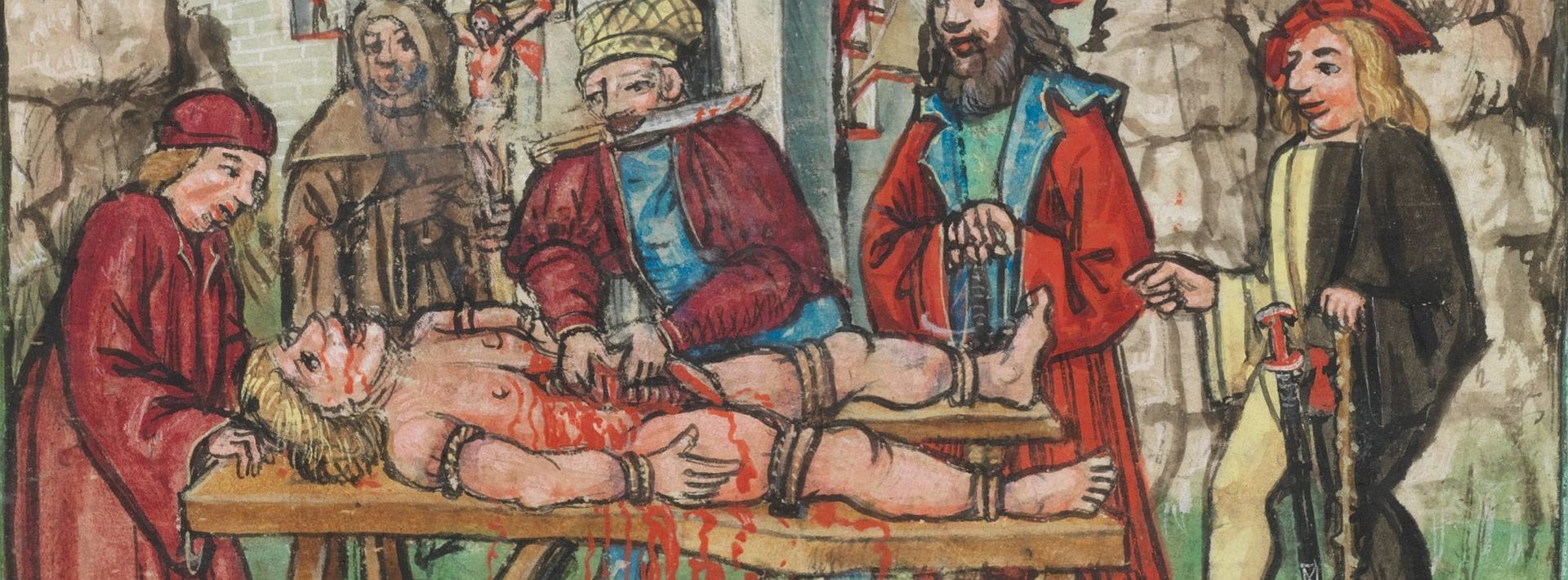

Just like any good craftsman, the executioner tried to do a "clean" job. When it came to torture, he was only allowed to go as far as it was useful—he wasn't supposed to kill them. The executioner had to be extremely careful that the tortured prisoners didn't die, so they could still be brought to their "real" punishment.