The Theft of the State Treasury

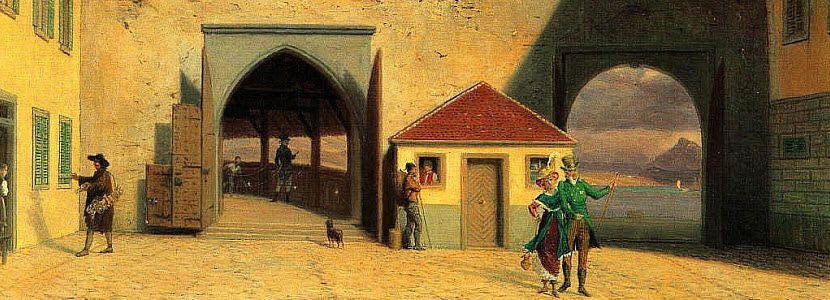

Lucerne, 1758. The Golden Time of the Republic was coming to its autumn. Wars and bad harvests in Europe meant that the soldier contracts, which the city lived from, were paid slowly. This made the state treasury, the heart of the Lucerne Republic, even more important.

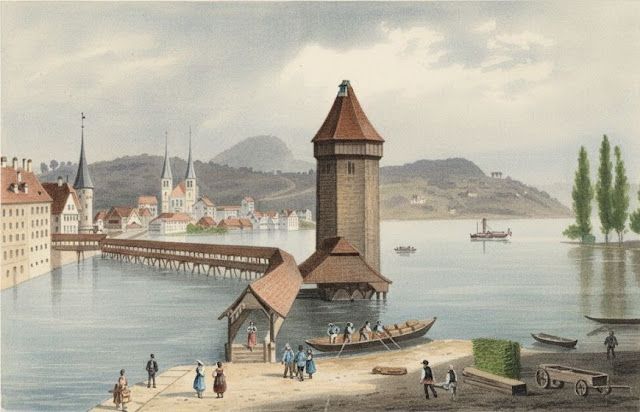

It was stored in the safest place you could think of: in the upper room of the Water Tower. The Reuss river flowed around it, and you could only reach it over the Chapel Bridge or by boat.

The Hole in the Attic

But no lock is safe from those who have the key. It began years before, an idea from the chaplain Beat Spengler, who was a student then. Together with his fellow student Ludwig Ales and the city employee Josef Anton Stalder, who kept the keys to the tower, they made the plan.

From the attic, they used a rope to go down into the treasure room. They drilled holes into the iron-bound chests, took gold and silver coins, and cleverly filled the bags with sand and stones until the weight was exactly right. Sometimes there were checks, but they only weighed the chests and did not check inside. They fell for the trick.

The Loan with Bad Consequences

For years, nobody found out about the theft. The theft became routine. Stalder told the new city servant Frölin about it, and soon a whole group of people knew: Stalder’s wife Maria and his daughter Veronika, Frölin’s wife Anna Maria Breitenmoser and her brother Alois, Stalder’s maid Elisabeth Bachmann, and a man named Nicolaus Schumacher.

The cheat was only found out when the Teutonic Order (Deutschritterorden) asked for a loan of 100,000 florins. The Great Council agreed on December 1, 1758.

Sand instead of Guilders

The next day, December 2, the councilmen opened the treasure room in the tower to get the loan. The quiet in the room turned to pure horror. When they wanted to count the coins for the loan, they found bags full of stones and sand. 50,000 guilders were missing – today that would be worth several million Swiss Francs.

The Hunt

The Council of Lucerne acted very hard. A hunt was started. They quickly thought it was their own employees. Josef Anton Stalder was arrested when he was trying to run away. But the city servant Frölin escaped at first.

The two clergymen, Spengler and Ales, also fled over Lake Constance. Stalder’s maid, Elisabeth Bachmann, went to Milan as soon as she heard her master was arrested. Alois Breitenmoser was also gone.

Through questioning, with and without torture, the whole conspiracy was found out. Frölin was finally found among soldiers in Hessen (Germany) and brought back to Lucerne.

.

The Price of Betrayal

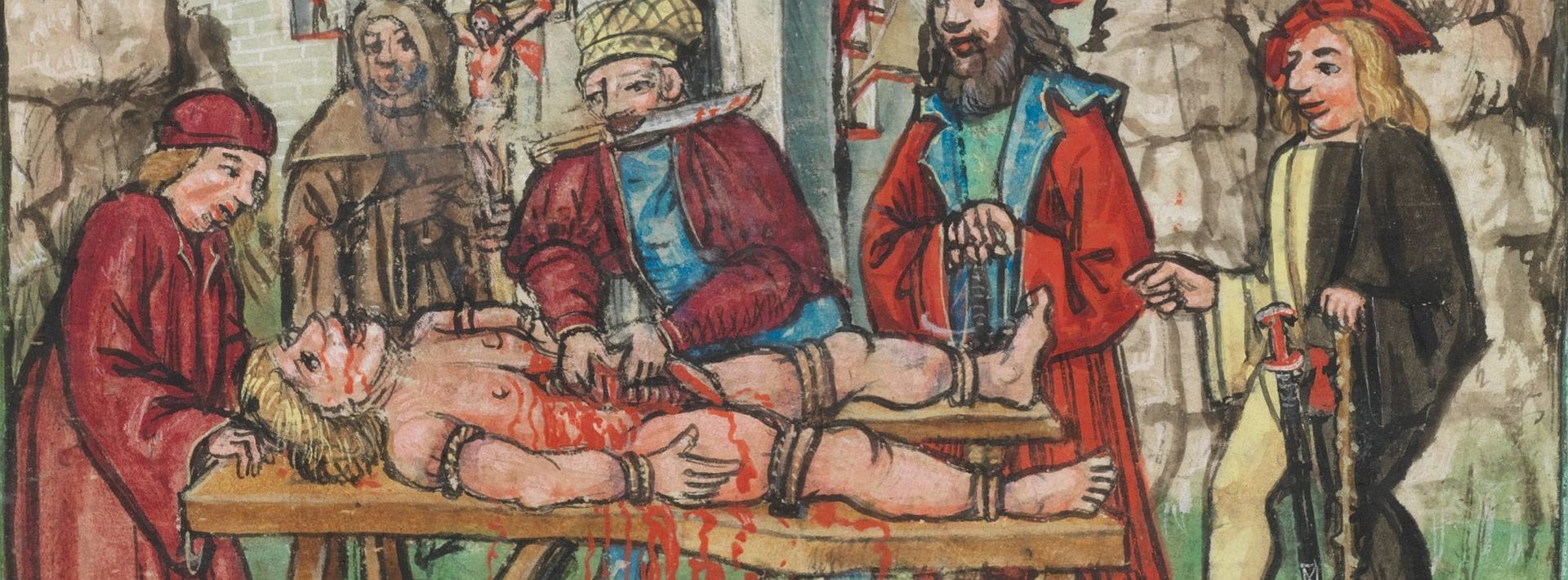

The judgments in spring 1759 were merciless and were meant to scare others.

Josef Anton Stalder, the leader and a citizen of the city, was punished cruelly: his right hand was cut off, he was strangled on a post, and his body was quartered and put on the wheel.

Anna Breitenmoser was beheaded.

Jost Ignaz Frölin and Nicolaus Schumacher were hanged.

Only Stalder’s daughter, Veronika Stalder, did not get the death penalty. She was the only one who showed real regret and was sentenced to life in chains.

Sentenced and Disappeared

The executioner carried out the sentences. Chaplain Spengler, the man with the idea, later died in a monastery in Vienna in church asylum. Ludwig Ales, the organist, disappeared and was never seen again.

Two other conspirators were never caught: Alois Breitenmoser and the maid Elisabeth Bachmann. What happened to them is still unknown today. We only know that Breitenmoser fled early and Bachmann made it to Milan.