The Executioner's Code

Just like any good craftsman, the executioner tried to do a "clean" job. When it came to torture, he was only allowed to go as far as it was useful—he wasn't supposed to kill them. The executioner had to be extremely careful that the tortured prisoners didn't die, so they could still be brought to their "real" punishment.

If necessary, he even had to patch them up, which is how he gained medical knowledge.

While doctors at the time were forbidden from dissecting bodies, executioners learned a lot about anatomy and healing. They passed this knowledge on to their sons.

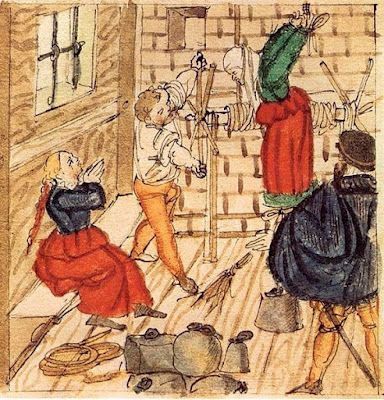

Lucerne Schilling, 1513, Folio 210r (p. 425). A servant in Bellinzona who intended to betray the city to the French is cruelly disemboweled and quartered (1500).

In 1782, a "Master" Leonard Vollmar, who beheaded Anna Göldi (the last "witch") in Glarus, asked permission to bring his 19-year-old son along, "who would like to learn how the thing is done."

The highest and most "honorable" job for an executioner was the art of beheading by sword.

This had to be done in one single strike, cutting the head completely from the body—so clean that a wagon wheel could supposedly roll through the gap. The executioners' sons practiced this on animals.

A good executioner understood the seriousness of his job and performed it factually, seriously, and according to a fixed ritual.

The Big Moment

Picture this: Hundreds of people are watching the execution. The judge, the executioner, and the condemned person are standing high up on the scaffold.

The executioner places his hand on the condemned person’s shoulder and tells him to kneel.

Then he stands behind him, takes a step, and raises the execution sword.

This is the executioner's moment.

Hundreds of eyes are focused on him.

Dead silence.

He breathes out deeply, his muscles tense, adrenaline shoots through his body.

He looks at the judge.

A nod.

Then

Sssfffffft.

An almost silent whistle cuts the air.

Thwack.

A short, wet sound. The body slumps.

Thud – – Thud – Thud.

The dull sound of the severed head rolling across the scaffold.

The crowd screams and cheers. For the executioner, it's a rush.

Now he is the king—for one moment, the absolute superstar.

He enjoys this moment, knowing full well that in the next second, he will once again be the most dishonorable of the dishonorable: the outlaw, the outcast.