The Pilatus Legend – or How the Mountain Got Its Name

Mount Pilatus strongly stimulated the imagination of the people in Switzerland early on. This was because it seemingly rose gently from the flatlands, but then suddenly jutted steeply upwards in massive rock formations.

The ancients called it "Fractus mons" (broken mountain) or Frakmont. They considered it nothing more than a split and broken-up mighty hill.

Since the people of antiquity could not explain the elemental forces that once split the mountain, they saw in them the work of evil powers. Because fire, water, storms, and lightning had always terrified the residents, they believed that these forces were causing mischief on the mountain. In the ignorance of the Middle Ages, one thing was clear: spirits lived there. In the stories, one heard of dragons, ghosts, spirits, hobgoblins (Herdmännlein), and mischievous dwarves (Toggelis); even the Türst and the Sträggele caused trouble there.

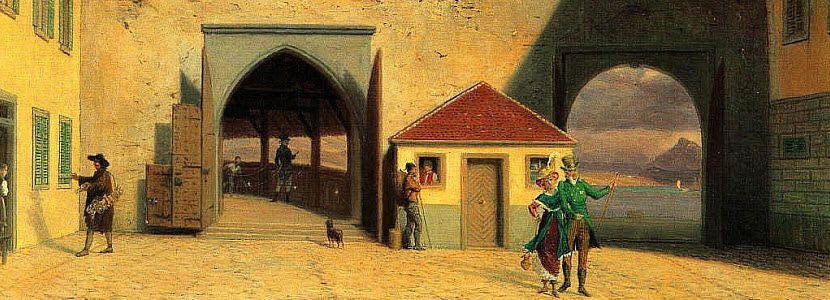

Lucerne Schilling Chronicle, 1513, Folio 89r, page 177. A heavy thunderstorm flooded the Krienbach stream. Debris (scree and wood) tore away the protective barrier and the bridge between the Barfüßertor (Barefoot Gate) and the Ketzerturm (Heretics' Tower) and caused great damage in the small town of Lucerne on June 24, 1473.

The Historical Fear of Pilatus

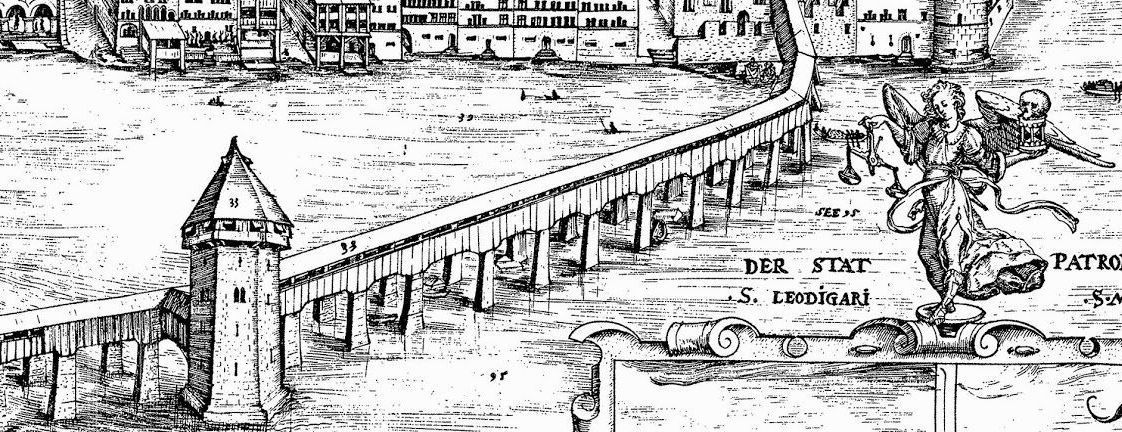

To properly understand the Pilatus legend, one had to empathize with the fears of the Lucerne population. Until about 150 years ago, the city was repeatedly affected by severe floods of the Krienbach stream. During thunderstorms on Pilatus, this stream swelled rapidly and carried large amounts of water and debris, which often flooded the entire small town. For example, in 1566, the barracks and the Spreuer Bridge were torn away.

According to the legend, a student from Salamanca spread this story about the curse of Pilatus in Lucerne. For the residents at the time, this legend was a plausible explanation for the destructive fury of the mountain. The danger ended only about 150 years ago, when the Krienbach was diverted and most of its water flowed into the Kleine Emme river near Malters. Today, the harmless remnants of the stream flow under Burgerstrasse at the needle dam into the Reuss river.

Ulrich Gutersohn (1862–1946), the Corporation Building, 1885. The Krienbach stream is in the center, with Pilatus in the background.

The Pilatus Legend – The Judgment and the Curse

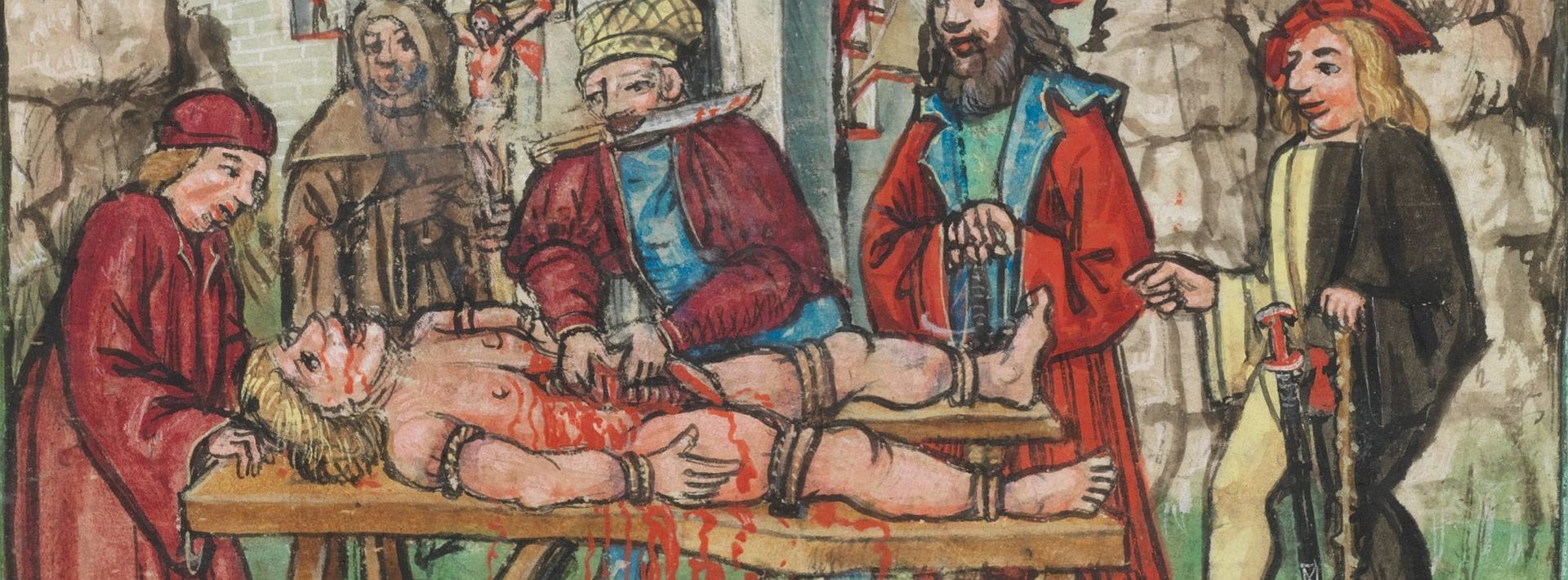

The legend said the mountain was the final resting place of the Roman governor Pontius Pilate, who had unjustly condemned Jesus Christ.

The sick Emperor Tiberius in Rome sent his servant Albanus to Jerusalem to bring the healer Jesus Christ to him. Albanus met the governor Pilate there, who did not want to give him an answer because he had unjustly condemned Jesus to death. Albanus found the woman Veronica. She told him about the death and resurrection of Jesus. Veronica possessed the veil that she had offered to Jesus on his path of suffering for him to wipe his face, and upon which the image of Jesus was miraculously imprinted.

Veronica accompanied Albanus to Rome. When the Emperor saw the cloth and looked at it devoutly, he was immediately healed of all his ailments.

The healed Emperor had Pilate brought to Rome to punish him. When Pilate appeared before the Emperor for the first time, he was wearing Jesus' garment. Although Tiberius wanted to condemn him, his anger vanished every time, and he could not harm Pilate. The Emperor knew nothing of the protective power of the holy robe. He had Pilate taken back to the dungeon.

On the second day, Pilate appeared before the Emperor again, and the anger disappeared again. Tiberius could not judge him again. Then Tiberius turned to Veronica and asked for advice. She realized that Pilate was wearing the holy robe of Jesus Christ. Veronica advised the Emperor to have Pilate take off the garment.

On the third day, the Emperor had Pilate remove the robe. As soon as Pilate had taken off the robe, the Emperor's wrath returned, and Tiberius sentenced him to death.

Pilate evaded the execution: Back in the dungeon, he killed himself with a knife.

The Spirit in the Mountain Lake

The corpse of Pilate caused great thunderstorms and terrible things wherever it was buried. Therefore, it was first thrown into the Tiber in Rome, but even there, the body could not be left because of the bad weather. Then the body was brought to the city of Lausanne and thrown into the Rhône river. Again, the devils returned and caused mischief.

Finally, the corpse was taken to the mountain near Lucerne and thrown into a lake. This mountain was called Fräkmünd, and the lake is called Pilatus Lake. People believed that if someone disturbed the spirit of Pilatus, it would bring terrible thunderstorms with hail and thunder.

How Not to Disturb the Spirit

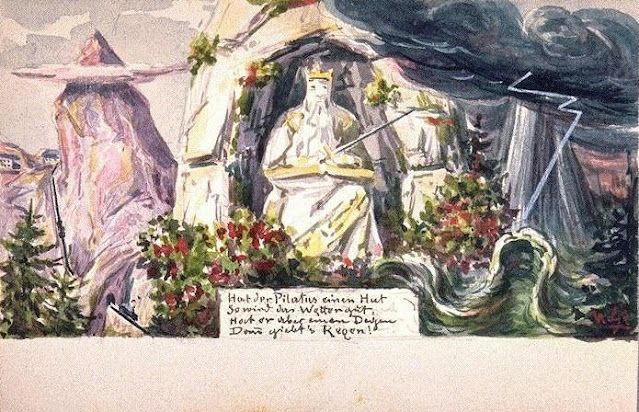

People believed that the spirit of Pilatus was allowed to rise up in the middle of the lake once a year, namely on Good Friday. Then he sat enthroned on his judgment seat in Roman governor's attire. For the rest of the time, he remained quiet and peaceful in the water—provided he was left undisturbed.

He was not allowed to be provoked under any circumstances. As soon as someone spoke loudly by the lake, called out his name, or threw wood and stones into the water, his wrath would break out: The sky turned black, lightning flashed, and thunder rumbled. Terrible storms and destruction fell upon the region of Lucerne.

For this reason, it was subsequently strictly forbidden to climb the mountain out of curiosity or recklessness.

The Fight Against Superstition

So much for the legend.

It is historically documented that it was forbidden to climb Mount Pilatus. Only the shepherds were allowed to stay there. The shepherds and herdsmen on the alpine pasture were sworn and obligated by the government not to let anyone go up to the Pilatus Lake.

The prohibitions were taken very seriously:

- Already in 1387, six clergymen were imprisoned and expelled just because they wanted to visit the notorious lake.

- In 1564, two men were imprisoned because a heavy thunderstorm broke out over the mountain after their forbidden excursion to the lake.

But this superstition lost its power, mainly through the work of the Lucerne city parish priest Johannes Müller. In 1585, Müller climbed up to the lake with a large escort. He demonstratively challenged the spirit of Pilatus by throwing stones into the shallow water and instructing people to wade into the lake. Nothing happened, however: Neither a storm nor bad weather broke out, and the sky remained cloudlessly clear.

To finally put an end to this popular belief, which was recognized as nonsense, the Lucerne Council decided to abolish all prohibitions. Furthermore, the Council ordered the lake to be drained in 1594.

Today We Know: Where the Name Pilatus Comes From

The name Pilatus does not derive from Pontius Pilate.

It stems from Latin:

- Latin: Pileus means "the cap."

- Derived: Pileatus means "the one wearing a cap."

The mountain was named this because it often wears a cloud cap. There is also a proverb about this that every Lucerner knows:

Hat der Pilatus einen Hut, (If Pilatus wears a cap,)

wird das Wetter sicher gut. (the weather will surely be good.)

Hat der Pilatus einen Degen, (If Pilatus wears a sword/dagger,)

wirds bestimmt regnen. (it will certainly rain.)

Hat der Pilatus eine Kappe, (If Pilatus wears a hood/bonnet,)

wird das Wetter Knappe (instabil). (the weather will be unstable/scarce.)

Ulrich Gutersohn (1862–1946), the weather proverb, 1900. On Good Friday, Pilatus is enthroned on the judgment seat.

The Pilatus Lake is now dried up but is still marked on every map, including on Google Maps.

For the sources please refer to the German version of this post.

Header image: © Lucerne Tourism / Ivo Scholz | Switzerland Tourism